Quality vs. Quantity

Using arbitrary logic for an arbitrary question

Hello everyone, today’s broadcast will be about trying to solve the timeless discussion arguing between quantity and quality. This debate can be applied to almost any facet of life, whether its education, accomplishments, gym reps; anything. One way of looking at this is by looking through the lens of war- Not only is war a fertile environment for innovation, but quality and/or quantity are central tenets to strategy.

It goes without saying that war encompasses much more than just coldly conducting a cost/benefit analysis- the morals, ethics and emotions are an inseparable aspect of war, for for today’s broadcast we will be focusing on the innovation that results from conflict.

War breeds desperation, and desperation breeds ingenuity, whether its discovering ways to use as little scarce resources as possible or finding the upper edge that can tip the scales. Together with the influx of money into the military, especially in total war or near total war economy states, this creates a generative environment for innovation or extreme production.

Setting the Scene

For this exercise, I believe attaching definitions or a frame of reference to the ideas of ‘quantity’ and ‘quality’ would be useful. both of these ideas can be explained by 3 factors which need their own sub-definitions:

Cost: cost to produce a single unit

Number: number of units at any one time, within reasonable timeframes of production for the unit in question- as an example, building battleships takes years, so in a timeframe of a thousand years, you could make hundreds and hundreds, but in a timespan of a month, you would be lucky to have two sheets of metal welded together.

Value: Dollar value of destruction directly attributed to a unit before it is destroyed/spent/used.

Using these parameters, for this broadcast we are going to define ‘quality’ and ‘quantity’ as the following:

Quantity: the goal of maximising the ‘number’ of units, typically by working to minimise the ‘cost’, irrespective of a single unit’s ‘value’. In extreme cases, a singular unit may have a minimal or even zero ‘value’. The idea is that value will be achieved by overwhelming quantity, where it is difficult or impossible to attribute success to any one unit, and each unit would not have the same impact without all the other units simultaneously participating.

Quality: The goal of maximising ‘value’- This usually means ‘cost’ runs high, not only in production but in development, and the ‘number’ produced is often much lower than lower quality counterparts. The idea is that value is achieved with much smaller numbers, and this might mean that the overall cost of the exercise is lower than if the quantity option was taken.

Quality vs Quantity in History

Looking back in history, it can be pretty difficult to discern which is better, with numerous examples illustrating the effectiveness of an unrelenting mass of large armies, or the sharp, precise victories of a highly trained force:

Quality

Perhaps the most infamous example that could be used that illustrates the devastating impact quality can have is the nuclear bomb: A result of a massive ‘cost’, to create a few number of nuclear bombs, but their value is undeniable- being able to flatten cities. It represented the best quality option for the USA to force the unconditional surrender (again, morals and ethical judgements aside) with as little material and human cost to the United States.

Quantity

One prominent example of the suffocating effect of quantity is the mass production of T-34’s by the USSR. These tanks were designed with the express intention of mass production- even when flaws were identified, fixes were not implemented, as they would increase production times or costs. There was a constant drive to reduce the number of parts needed for a tank, working to reduce complexity and time needed to assemble them. By the end of the war ~74,000 were produced, the second most produced tank ever, second only to its successor.

Although the T-34’s were a match for the earlier Nazi Panzers and tanks, they stood little chance alone against the later Tigers, Panthers and King-Tigers. However, with the number of these T-34’s being churned out in factories, they proved too overwhelming, and were often seen as the workhorse of the army that largely decimated the Nazi forces, from the Caucasus’s to the Reichstag.

The Cop Out

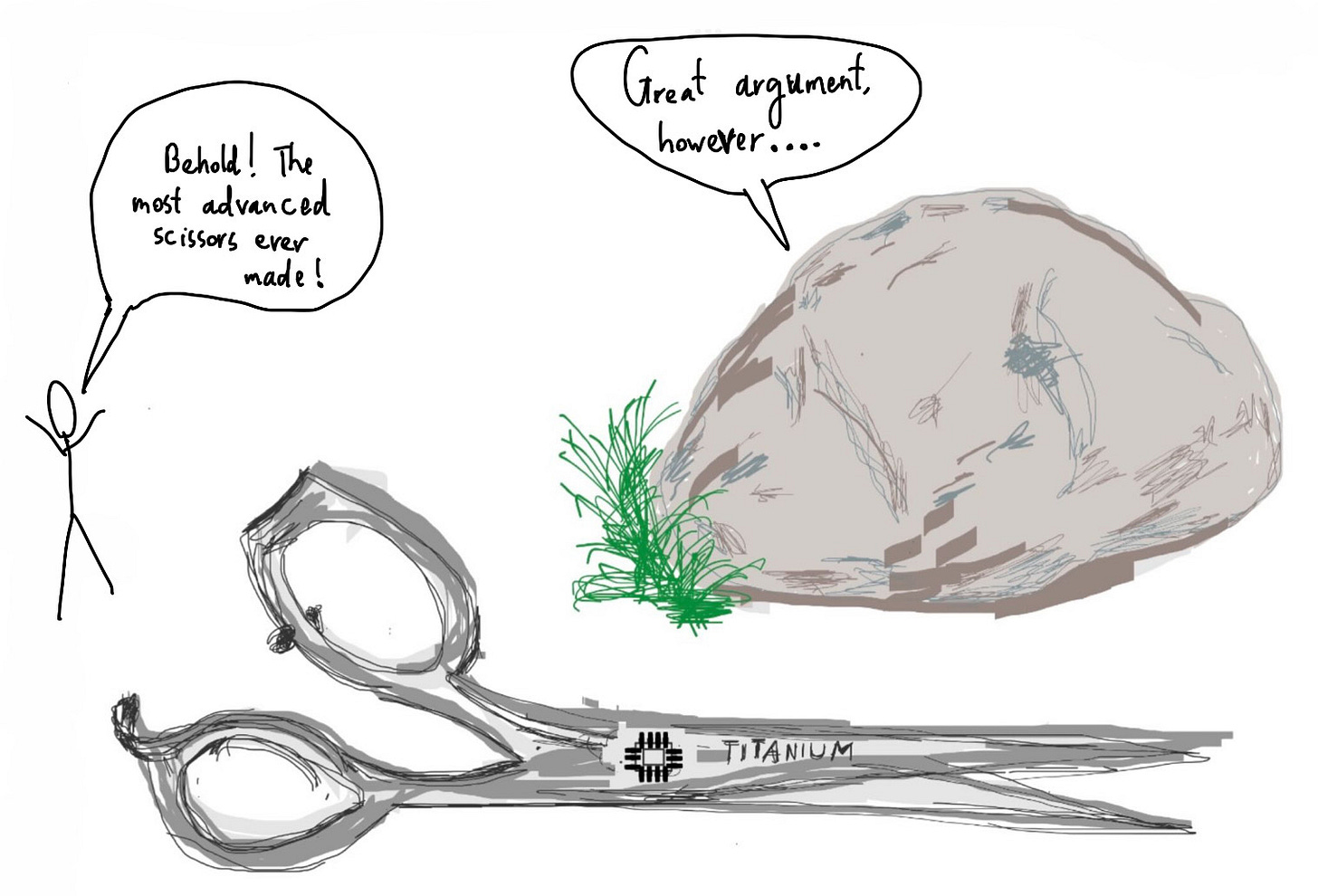

The easy answer of course, is to just smirk and say it’s all relative: it depends on how large the discrepancies are between the quality and/or quantity of the warring forces, not to mention the way they are used tactically in the micro-sense and strategically in the macro sense. And this of course is right- after all, you shouldn’t design the best or produce the most scissors if your enemy has a rock- but this answer is not correct in terms of answering the question. So as much as possible we will try to assume equal strategic competence (for now):

However, this relativity in quality and quantity creates interesting dynamics and phenomena: It could lead to quality or quantity that is irrelevant or misplaced, marginal or insufficient; even paralysing.

Irrelevant/Misplaced -

-Quality

One example of irrelevant or misplaced quality were the Imperial Japanese battleships Yamato and Musashi. Battleships can trace their heritage back to the age of wood and cannons- big, large, typically slow ships with a myriad of cannons meant to be the muscle of any navy. As the wood turned to steel, and cannons to artillery, battleships as we know them took form in the age of the dreadnoughts in the early 1900’s.

Yamato and Musashi were the final form of these class of ship: packing the largest displacement, with their largest guns able to fire rounds over 40km. However, by the time these sister ships were employed in combat, it was slowly becoming clear that the age of the battleship was being swept away by the aircraft carrier, but really the aircraft themselves.

Albeit a bit reductionist, aircraft carriers are little more than floating hangars and runways, with their sole purpose being to house and accommodate aircraft at sea. As simple as they are in premise, they changed the dynamics of naval warfare forever. What use are your 42km range guns when aircraft carriers can let loose dozens, even hundreds of aircraft from hundreds of kilometers away. these aircraft could destroy the battleship, without it ever seeing its opponent. When you can damage your enemy but they can’t touch you let alone see you, that’s quite the advantage.

Even Musashi and Yamato, the most advanced (highest quality) battleships afloat, with some of the heaviest anti-aircraft armaments, stood no chance- both were sunk due to air strikes by the US Navy. At the end of the day, even if a ship shot down 50 aircraft before setting off on its final voyage to the depths, the immense cost of losing a battleship completely outstrips the cost of the 50 aircraft lost (plus remember, the aircraft carrier is untouched)- a clear victory of quantity over quality. There are debates as to how the war would have went if Imperial Japan had prioritised aircraft carriers over battleships such as these.

Irrelevant/Misplaced -

-Quantity

One example of an irrelevant quantity were the Nazi German land forces with respect to Operation Sea Lion- the planned invasion of Britain. After the fall of France and the retreat at Dunkirk, Britain was the remaining unoccupied territory at the time. After initial hopes of Britain surrendering did not materialise, plans were drawn up for the invasion of the island. Post Dunkirk evacuation, where the vast majority of machinery, supplies and tanks were abandoned in France, around 80 heavy and 180 very light tanks (armed with only machine guns) were in Britain ready for their last stand - For comparison Nazi Germany had used ~2500 tanks for the invasion of France.

However, despite the overwhelming advantage in forces, they are incredibly vulnerable in an amphibious landing from Naval and airborne forces alike. As a result, Nazi Germany set out to achieve air superiority prior to the land invasion. However, due to heroics spear-headed by the Polish Division 303, Nazi Germany never succeeded and the invasion never came to pass- With the numerical superiority of their land forces never having an impact.

Marginal/Insufficient -

-Quality

A clear example of some things being better quality, but not impactfully so, were the later war tanks produced by Nazi Germany, with the Tiger, the Panther and the King Tiger being the most infamous. When these tanks were on the battlefield, they were powerful pieces of machinery, with superior firepower and amour, reinforced with stories of a single tank knocking out dozens of Soviet or allied tanks.

As it was clear to all that Nazi Germany could not outproduce the american workhorse or the soviet steamroller, it desperately attempted to create superior quality weapons which could turn the tide of the war. And although these tanks were a step above any other tanks on the battlefield on either front, far superior numbers of allied tanks, together with air support neutralized to a significant degree the impact these tanks had on the outcome of the war.

-Quantity

At the onset of World War 1, the Russian Empire had a numerical superiority in armies over the Germans and Austro-Hungarians ( Russia’s army had ~1.4 million men, while Austria-Hungary had ~450,000 and Germany split ~1.9million between the two fronts). Despite this advantage it ultimately proved insufficient to cover over the deficiencies in strategy and leadership, From Tannenberg up to the eventual defeat and withdrawal of the Russian Empire and USSR from the war.

Paralysing -

-Quality

Perhaps the most interesting phenomenon: paralysing quality could be observed when something is of extreme quality (referring back to our sub-definitions): Extreme value, extreme cost, and incredibly low numbers, often a singular unit. When something is so overpowering and yet so expensive to produce, it becomes exceedingly hard to justify their use or deployment, in effect rendering them useless. Almost every scenario for these things is either too low impact, where cheaper options are much more justifiable, or the risk of losing the item is too great to risk even deploying, for fear of losing the item prematurely. ultimately, they are paradoxically too good to be useful.

So what examples of such things are there? For one, aforementioned nuclear bombs could be considered paralysingly(not sure if that’s a word) high-quality: In almost every scenario apart from total war or Armageddon, it is practically impossible to justify their use. Even Yamato and Musashi exhibited these traits, often never committed to battles for fear of losing them.

However one of the most prescient examples is perhaps Article 5 of NATO: the idea that if someone attacks one member of NATO, they are at war with every member of NATO. The consequences of enacting this article are huge: involving a significant percentage of the world’s armies, air force, navies and most importantly, nuclear weapons.

However, that’s what makes the wording of Article 5 so delicate:

‘Attack’ is the key word here. Are military drills conducted near your borders an attack? Are close flyby’s of your warships considered an attack? Are cyberattacks considered an ‘attack’? Is election interreference an attack? There is a muddy, gray area between an ‘attack’ and peace-time, leaving it ripe for exploitation. These Gray-zone tactics have been used by many, and it questions the effectiveness of Article 5 in defending one’s sovereignty in the first place.

One could counter by arguing that that’s all another country can do- provoke, subvert, but not outright invade. But there is nothing that states that these gray-zone tactics can’t shift over time and envelop more and more brash actions or annexations in the future: poke enough holes in a wall, and it’s integrity will fail.

Drones- The Sweet Spot for Quality and Quantity

There are also times when things are both high quality and quantity, most often occurring when new technology is introduced that changes the rules of engagement. This happened with planes, anti-tank weapons, and currently with drones:

Drones are a new, still raw technology that has transcendent impact on warfare: capable of being precise while speedily reaching areas by air that are difficult to reach even on foot. And they can be devastatingly cheap too: even commercial drones with grenades fitted can be used to take down a modern tank with their hatch open: Quantity is easy to achieve, and if a drone can down a tank or even a whole ship, the quality is there too. Even for Russia, trading ships for drones is not something they can sustain.

Reflections

Perhaps we need to reshape our view of quality, not of a ceiling raiser, but of a floor raiser: perhaps quality isn’t about being the absolute best in something, but its about being decent or good in every facet of existence. Take the Sherman for instance:

The Sherman didn’t boast the firepower, armour or speed. But it’s key strengths were reliability, adaptability and its comparatively low cost, with the first two strengths only reinforcing the latter: Low cost results in cheaper repairs, with repair parts being easily made, modified and refitted. Even if Nazi tanks were twice as good as the Sherman, Shermans outnumbered their tanks more than threefold. And the adaptability of the Sherman ensured that they provided value in a myriad of ways, whether as mine-exploders, recovery vehicles; bridge carriers.

Quality is much more time-prescient: It is also invariably subjective, defined by the span of time one is looking at. Quality is often seen as the key- it can be decisive, crushing, dominant in almost every scenario. however, this is well understood by everyone. So in the game theory of life, everyone is racing to one-up their competitors quality, creating an accelerating spiral. It’s the qualities’ strength, influence and attractiveness that that makes the inherent value of quality so fleeting, so delicate- much like a house of cards, easily toppling over by an incoming rush of the 'newest quality’ on the bloc.

Quantity has much more inertia than quality in this sense. It’s staying power is much stronger, as even if others have higher quality or quantity forces than you, it is much much harder to overwhelm you due to the sheer numbers involved. Quantity is also more forgiving- you can afford to lose thousands on a gamble if you have millions, but not if the gamble could cost you half of what you have.

Chicken or Egg

One realisation that has struck me is the spiralling, almost chicken-or-egg relationship between quantity and quality: Quality can almost be seen as a means to an end, for instance one finds a good quality product then aims to produce as many of them as possible. But it’s a matter of when you start and when you end really:

As a starting point, lets argue that the end goal is to make something of high quality, for instance an effective vaccine against stupidity. However, one could just as easily argue that the actual end goal is to produce a vast amount of these vaccines, hence quantity. However, is the persons ultimate goal or motive for doing this to cure everyone’s stupidity (quantity), or to make himself the richest person in the world selling these stupidity vaccines (quality)? There really is no definite end to such an argument. And this argument can keep going and going, going down more and more routes, reaching the absurd, until it’s apparent that you yourself might need that vaccine sooner rather than later.

Overall, if I did have to give an ultimate answer to the question: Quality in the short term, quantity in the short term. In the short term, make sure you do the best you can in what you can do, and in the long term make sure you’re able to say you can do or have tried a vast variety of things.

I reckon I haven’t exactly solved the challenge of life, so I’ll say I came close.

Make sure to give this broadcast a coherence score!

That’s all from me for now, but stay tuned for future broadcasts,

This has been Kunga’s Written Radio,

Check out our last broadcast here →